Almost a year before the first votes of the 2020 -presidential contest, Democratic candidates are all over the map. There’s Elizabeth Warren in a drafty warehouse in Des Moines, Iowa, boasting to more than 1,000 people about forcing out a bank CEO. In South Carolina, Cory Booker’s in a college auditorium bringing the crowd to tears with his tale of the murder of a young boy from the Newark, N.J., projects. Sherrod Brown’s in an Ohio union hall, wondering in his raspy baritone if his party has lost touch with Middle America.

The 2020 Democratic primary will be unprecedented. The field is likely to be the largest in history, there’s no front runner in sight, and the stakes could hardly be higher. It’s not just that many Democrats argue Donald Trump is a threat to American democracy. The party’s very identity is up for grabs, as a vast and historically diverse crop of candidates brings big, new ideas to a demanding, divided base. “The Democratic Party is going through a very large transformation,” says party operative Simon Rosenberg, who’s backed the winning candidate in every primary since 1988 but has no favorite this time. “The era of Clinton and Obama is ending and ceding to a new set of dynamics. A new Democratic Party is being forged in front of our eyes.”

Illustration by Tim O’Brien for TIME

The candidate voters choose to take on Trump may set the nation’s ideological direction for years to come. Yet for the first time since 1988, there’s no clear favorite. Former Vice President Joe Biden holds a wide lead in early polling, and his would-be rivals anticipate he has secured $25 million in early donor commitments if he takes the plunge. Those close to Biden expect him to join the race. But while party insiders think he has a good shot, he’s hardly a shoo-in. Biden’s opponents privately believe much of his support will melt away once other candidates become better known. They also plan to remind voters how Biden, 76, grilled Anita Hill, cozied up to Wall Street and pursued tough-on-crime policies in the 1990s.

But Biden’s biggest liability might be the idea that he represents the party’s past, not its future. The notion of nominating an old, white male in the age of Trump leaves many Democrats cold. The cultural energy on the left is about resisting white nationalism- and toxic masculinity in the name of racial justice and gender equality. It’s about formerly marginalized groups demanding to see themselves in their leaders, and millennials tired of baby-boomer rule. Biden would be a throwback to an era of incrementalism and hierarchy that the new generation of Democrats is aching to leave behind.

The 2018 midterms revealed three major forces creating today’s party. The biggest was the power of women, who emerged in unprecedented numbers as candidates, organizers and voters. Second was the rise of a vocal, ambitious group of young progressives, exemplified by the media-savvy 29-year-old Congresswoman -Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez. But third—and larger in numbers than the “AOC” -faction—was the crop of political newcomers who cast themselves as pragmatists, many of them military or national–security veterans. These forces are pulling the party in different directions, and the struggle between them will shape the 2020 battlefield.

Watch: ‘I Am a Candidate’: The 2020 Race Begins

Unlike in elections past, the party establishment isn’t steering the race with money, endorsements or political machinery. Democrats’ elder statesmen are distant from the rising energies. President Obama is still beloved and has offered advice to several contenders, but sources say he’s unlikely to take sides publicly or privately. Both Clintons feel like yesterday’s news, each saddled with distinct political problems. The Democratic congressional leaders, Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, are products of a different era. In these days of social–media outrage and political cyberwarfare, everyone has a voice—but no one knows whom to trust, much less follow.

Fittingly, it’s women, minorities and younger candidates who have jumped into the race early, while many white male hopefuls remain on the sidelines, gauging the terrain. By the time Senator Bernie Sanders entered the fray on Feb. 19, there were already five women, two African Americans, a Latino and a gay millennial among the 10 major declared candidates. Some moderate, white, male candidates suspect there’s room for only one of them in the race: former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg and former Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe are unlikely to run if Biden gets in, according to sources close to both men. “At the end of the day, it will be about who can bridge the coalitions in the Democratic Party,” says Ohio Congressman Tim Ryan, who is mulling a run himself but is aware that being a straight white male could be a liability for the first time in history. “Those are things I cannot change,” he chuckles.

As much as they would like to move away from white male dominance, some rank-and-file Democrats worry that doing so would hurt the party’s chances against Trump. They fear that a woman or nonwhite candidate would be damaged by Trump’s sexism and race-baiting. And to the party faithful, winning is everything. “That’s the first, second and third quality people are trying to assess each of these candidates by,” says Jeff Link, an Iowa-based Democratic strategist who’s watching the hopefuls parade through his state and has not yet chosen a favorite. “People are anxious to kick the tires, vet the -candidates—and see who really is the person who can best take on Trump next year.”

A few key factors will define who ultimately becomes the front runner. First among them is the divided, demanding Democratic base, with factions ranging from centrists to socialists. Then there’s the process itself, a tangle of new rules and changing calendars. There’s the money chase, scrambled by surges in Internet–fueled small-donor cash and candidates’ turn against corporations, lobbyists and interest groups. Finally, there’s the challenge posed by a singular opponent.

The stories below investigate each of those forces, offering a trail map of sorts for a campaign that is sure to get rough. “Everyone’s behaving nicely now,” Rosenberg says, “but by the fall, this will be a tough, hard–hitting primary.” The debate clashes, micro–gaffes, scandals and policy disputes are yet to come, and the sprawling field only increases the chance of an unpredictable result. The bigger and messier the contest gets, the likelier it may be that the Democrats get the one thing none of them wants: a second Trump term. —M.B.

—With reporting by Philip Elliott/Washington

The Voters: A Divided Democratic Base is Luring Candidates to the Left

Winning a presidential primary isn’t magic: you figure out what voters want and then give it to them. But that’s no simple task for the Democrats seeking the White House in 2020. This isn’t the same party Bill Clinton or Barack Obama led. It’s not even the same one that nominated Hillary Clinton less than three years ago.

The party’s base is more diverse and more female than ever before, with newly assertive feminist and racial–justice voices demanding representation and respect. New policy ideas are flying: one cycle after Clinton’s liberal incrementalism barely beat out Bernie Sanders’ socialist vision, the party’s politicians and policy wonks are debating a range of ambitious ideas. A resurgent democratic–socialist movement has a high-profile presence not just on Twitter and among activists but also in elected office, and it’s advancing once marginal ideas toward the mainstream: big tax hikes on the rich, an end to private health insurance, guaranteed jobs for all and a climate–focused revamp of the economy.

“Progressive ideas are now more mainstream,” says Karine Jean-Pierre, a former Obama campaign and Administration official who serves as chief public-affairs officer for the progressive group MoveOn. “Many are popular with Democrats and even Republicans and independents. It says a lot about how far we’ve come as a country and a party.”

The party’s center of gravity may have moved left, but the ideological drift shouldn’t be overstated. “There are a lot of myths about the Democratic primary electorate, including the narrative that it’s super liberal,” says veteran pollster John Anzalone, who conducted 100 focus groups before the 2018 midterms. The share of Democrats who call themselves “liberal” or “progressive” tends to be about half, which is higher than it’s been historically, but hardly dominant. (By contrast, about three-quarters of Republicans call themselves “conservative.”) The other half of Democrats consider themselves moderate or even conservative. “We’re not the Republicans, with their litmus tests,” Anzalone says. “There might be some single-issue voters on the margins, but most primary voters are pro-choice, pro–gay marriage, pro–gun control and pro-environment. Beyond that, people really aren’t hung up on whether you do Medicare for All or just protect and improve Obamacare.”

Another myth is that the party’s increasing diversity is driving its leftward lurch. In fact, it’s the opposite: non-Hispanic white Democrats (about 60% of the party) are far more likely to call themselves liberal than black and Hispanic party members. While young Democrats are overwhelmingly liberal, about 60% of the party’s primary voters are still over 50.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren announces her official bid for President in Lawrence, Mass. on Feb. 9, 2019.

Scott Eisen—Getty Images

Some potential and declared 2020 candidates have responded to this mix by positioning themselves on the left end of the policy spectrum, like Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Kirsten Gillibrand. Other hopefuls are playing to the middle: Joe Biden, Amy Klobuchar, Mike Bloomberg, John Delaney. (When many Democrats raced to embrace the Green New Deal, Delaney, a former Congressman and banker, came out against the plan.) Candidates like Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Beto O’Rourke may try to straddle the divide, betting that the ideological tests imposed by online activists aren’t as important to actual voters.

That suspicion is supported by interviews with voters on the early campaign trail. At a recent Warren rally in Des Moines, Iowa, Jen Kownacki, 45, said ideology was less important to her than character. “I’m looking for someone that has strong values and stances they’re going to stick to,” she said, standing in a line that stretched around the block. At a Booker event in rural Denmark, S.C., Yokina Williams said she was looking for an antidote to President Trump’s divisiveness. “I’m a liberal,” she said, “but I’m looking for a candidate who can unify the country.”

Many primary voters express a similar yearning for bipartisanship, saying they want a positive and substantive message rather than someone who simply bashes Trump. The anti-Trump gadfly Michael Avenatti, who flirted with a presidential run, argues that the party needs a fighter to go toe-to-toe with Trump, and has taken to mocking candidates like Booker who preach harmony. But to many primary voters exhausted by Trump, a dose of “hope and change” is appealing.

As always, style and charisma are likely to matter to voters at least as much as policy papers and voting records. “These candidates are going to try very hard to distinguish themselves from each other, but their positions are pretty similar,” says Democratic strategist Rodell Mollineau. “It’s going to be a lot more about the framing of your worldview than one specific vote.” —M.B.

The Rules: A New Primary Process Favors Campaigns That Master It

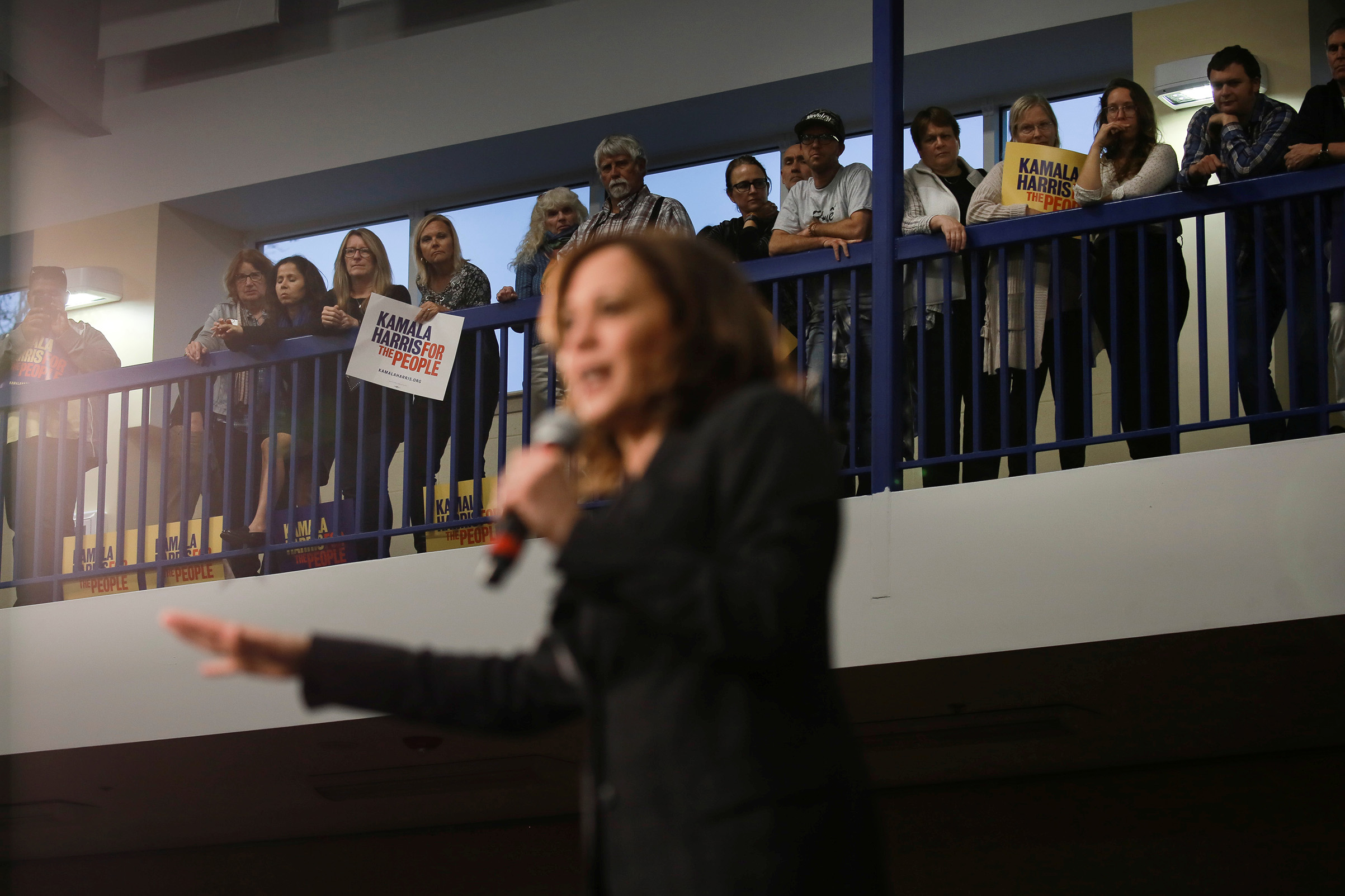

To rival campaigns, one of the clearest signs that Kamala Harris could be a formidable candidate was not her early fund-raising haul, the endorsements she’s racked up or the crowd of 20,000 that cheered her announcement speech in Oakland, Calif. It was the hiring of an obscure adviser named Dave Huynh.

Back in the 2016 primary contest, Delegate Dave, as he was known around Hillary Clinton’s Brooklyn headquarters, was charged with ensuring that no stealth Bernie Sanders backers were hiding in Clinton’s delegation to the Philadelphia nominating convention. The Howard University School of Law grad then spent much of 2017 helping to rewrite the rules of the Democratic Party. Now Harris has enlisted him to vet, befriend and monitor the roughly 3,800 “pledged -delegates”—a collection of Democratic activists and -insiders—who represent their states’ will at the party’s nominating convention.

The wide-open field of 2020 Democratic candidates makes masters of the party’s arcane presidential–primary rules more important than ever. The fact that those rules won’t be finalized for months only raises the stakes. Eleven states and some U.S. territories have yet to decide when they’ll hold their nominating contests. Other states have yet to decide whether they’ll hold primaries or caucuses. The Democratic National Committee has a May 3 deadline for state parties to file their plans, but party officials expect a handful to miss that deadline.

The resulting uncertainty is forcing campaigns with finite resources to make key strategic decisions without basic facts. Caucuses and primaries require entirely different campaign tactics and staffing levels, for example, and candidates don’t know yet when they’ll need bodies on the ground to compete in certain states. Even the big event remains up in the air: unlike the Republicans, the Democrats have not even picked the city where the convention will be held. “A lot needs to be determined,” admits a top Democratic campaign official.

Sen. and Democratic presidential hopeful Kamala Harris campaigns at a town hall in North Charleston, S.C., on Feb. 15, 2019.

Elijah Nouvelage—Reuters

Much of the blame, grumbling campaign staffers say, falls at the feet of the Democratic National Committee, which is still licking the self–inflicted wounds of the 2016 spats between Clinton and Sanders, whose supporters claimed the organization’s rules were rigged against him. DNC chairman Tom Perez won his election the following year in part by promising to reconsider the rules. After contentious public debate, the DNC ultimately settled on the biggest revamp of the process since 1980. “We can’t win if we don’t earn the trust of grassroots voters from across the country,” Perez says. “That’s why we’ve spent the last two years making historic reforms to the party.”

Some of those reforms are still coming together. In 2020, for example, the party’s roughly 760 superdelegates won’t be able to vote for a nominee until after he or she has won a majority of the regular, pledged delegates. That should prevent the party elites, like ex-Presidents and current members of Congress, from lifting a preferred candidate to victory or countermanding regular voters. But other reforms are still being hashed out. The DNC is pressuring states to move away from caucuses, which favored Sanders’ die-hard supporters. Colorado and Minnesota have announced they will hold primaries instead, and Maine, Idaho, Nebraska and Washington are poised to follow.

The irony of these changes is that a rules overhaul initiated by Sanders supporters and designed to democratize the nominating process may end up hindering “movement candidates” and helping structurally superior campaigns. Maybe. Truth be told, everyone is still trying to game out who gets the advantage with the new rules. “It’s like ‘Thunderdome’ with fractions,” says one DNC member.

It will only get worse if the race drags into the summer of 2020. Making it that far may be a challenge for many: -California has jumped forward in the schedule, holding its primary in March instead of June, and competing for its 362 delegates will cost dump trucks of cash for ads and campaign staff. But three-quarters of those delegates, like others around the country, will be awarded by congressional district, to those who earn 15% support or more, meaning the historically large field is likely to split the vote into ever smaller fragments. The nightmare for Democrats: it’s entirely possible that delegates arrive at the party’s convention in July with the outcome of the race still uncertain. The nomination could require multiple ballots for the first time since 1952.

Which is why insiders like Dave Huynh loom so important this cycle. Unlike their Republican counterparts, Democratic pledged delegates are not required to stick with the candidates they told primary voters they would back. With superdelegates barred from breaking the logjam, it could be personal relationships established over the years, like Huynh’s, that tip the outcome on the convention floor.

Wherever that might be. —P.E.

The Money: Why Winning Campaigns Will be Powered by Small Donors

As Cory Booker’s inner circle planned his presidential bid on multiple conference calls in recent months, talk inevitably turned to money. To win, the aides concluded, the Senator needed to build a grassroots fundraising network broad enough to generate hundreds of millions of dollars. So far, things appear to be going according to plan: since Booker jumped in, 81% of the campaign’s donors were new. “We’re going to power this election principally by low-dollar contributions,” Booker said on his first trip to Iowa.

Left, right or center, the strategists advising candidates- this cycle estimate successful ones will need about $100 million just to get to Iowa’s leadoff caucuses on Feb. 3 and an additional $50 million to reach Super Tuesday a month later. Top staffers at major campaigns tell TIME that small–dollar fundraising is a cornerstone of their strategies. The Democratic National Committee is using small-dollar fundraising as one of the criteria to qualify for the first debates in June. “If someone isn’t building this,” an adviser to one 2020 campaign says of its digital donor machine, “they’re doing it wrong.”

The power of small-dollar giving was evident in 2018, when the left’s online fundraising platform ActBlue processed 42 million contributions totaling an eye–popping $1.6 billion. By some estimates, that haul could double in 2020.

Sen. Cory Booker speaks during a news conference outside of his home in Newark, N.J. on Feb. 1, 2019.

Julio Cortez—AP

The emphasis is a dramatic shift from past cycles, when Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton worked the fund-raising circuit to woo major donors and attended events for super PACs working on their behalf. This time, the Democrats are mirroring the mood of their base by heeding Senator Elizabeth Warren’s call to swear off contributions from lobbyists and corporate PACs. Former Housing Secretary Julián Castro has already returned some lobbyists’ donations. When supporters signed up to receive text messages from Senator Amy Klobuchar’s campaign, this was their first reply: “This team is powered by YOU (i.e. NOT Super PACS).”

There’s a clear leader in the small-dollar cash chase: Senator Bernie Sanders. A day after jumping into the race on Feb. 19, he had raised $6 million from more than 225,000 donors. Beto O’Rourke mustered 750,000 such donors in his 2018 Senate campaign. Kamala Harris raised $1.5 million online in the first 24 hours after announcing her presidential run on Jan. 21, with an average contribution of $37.

Not that big-dollar donors won’t weigh in too. But even they view online giving as a cost–saving barometer of viability. “Small-dollar donors and newbies are going to power these campaigns,” says a veteran Democratic fundraiser. “Until the veterans come off the sidelines, probably around Halloween.” —P.E.

The Opponent: Can Any of These People Beat Donald Trump?

More than anything—more than policy or charisma or age or race or gender—Democratic voters say they care about whether a candidate can beat Donald Trump. The problem is nobody knows how to beat Trump in an election, because nobody’s ever done it.

Trump’s 2016 opponents tried everything. His Republican primary rivals tried ignoring him. They tried reasoning with voters, pointing out that he wasn’t a traditional conservative. Some tried ridiculing him; Marco Rubio insulted the size of his hands. Ted Cruz tried aligning himself with Trump, which was good enough for second place. In the general election, Hillary Clinton pounded Trump’s character and warned that he posed a danger to U.S. security. Like Cruz, Clinton built a data-driven, voter–targeting operation with expensive staff, offices and technology, but these state-of-the-art campaign organizations were no match either: Trump beat Clinton with little more than a Twitter account, a personal jet and perhaps a little help from abroad.

The shock of Clinton’s defeat left Democrats feeling gaslit and insecure. Nothing made sense; Trump seemed impossible, maybe invincible. “Democrats were second–guessing themselves a lot,” says Seth Masket, a University of Denver political scientist writing a book on the evolution of the party between 2016 and 2020. “They didn’t trust their own political instincts.”

Trump wasn’t on the ballot in 2018, but the Democrats’ success in taking back the House of Representatives reassured anxious partisans that he wasn’t all–powerful. The party’s strategists took a simple, disciplined approach: candidates, particularly in swing states and districts, ignored Trump as much as possible. Instead they focused on health care and emphasized pocketbook issues. The gambit was successful in the Rust Belt states that gave Trump the presidency-: Democrats swept every statewide contest in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. They also dominated the suburban areas that are home to about half of the electorate, winning congressional districts from Oklahoma City to Orange County, California. “Donald Trump was the background music,” says Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson. “Our focus was on health care and taxes and issues that impacted people’s lives, even if they weren’t hearing about them on the nightly news.”

President Donald Trump leaves after speaking from the Rose Garden of the White House in Washington, on Feb. 15, 2019.

Brendan Smialowski—AFP/Getty Images

So far, the 2020 contenders are performing variations on that 2018 playbook: trying to define themselves on substance, issues and policy rather than competing to articulate the most savage indictment of Trump. Amy Klobuchar, in her announcement speech, said she was running to “take back our democracy.” Kamala Harris insisted, “America, we are better than this.” But the problems they pledge to solve tend to be traditional liberal priorities, like getting money out of politics and making health care more accessible.

Demographics are also on the mind of anxious Democratic voters. Some worry that Trump’s skill at tapping voters’ latent misogyny would make it a mistake to nominate another woman. Others fear his race-baiting would hurt an African–American or Hispanic nominee. And Democrats’ decades-old debate over the relative importance of blue collar whites and lower–propensity minority voters rages on. Trump seems to delight in ridiculing Elizabeth Warren, while White House advisers say he most fears Joe Biden as an opponent.

Then there’s the wild card: What if Trump isn’t on the ballot? House Democrats have begun hearings into the President’s affairs. Special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe into Russian election meddling may be nearing completion. Impeachment proceedings appear possible, even likely. Already, Trump has drawn a dark-horse Republican primary challenger, former Massachusetts governor Bill Weld. The President enjoys strong support from most Republicans, but a recent poll found a third of GOP voters open to an alternative.

For now, most Democratic voters are watching the new 2020 candidates and weighing which ones seem best poised to vanquish the President. But electability, says former Obama strategist David Axelrod, is in the eye of the beholder. “In my experience,” he says, “people tend to decide who they like, then rationalize how that person can win. That’s what they mean by ‘electability.’” —M.B.

More Must-Reads from TIME